Zbigniew Rybczyński's Orchestra

Today everyone lives in a high-definition world of 4k streaming, 1080p resolution graphics, and the seemingly endless technological horizon of greater and greater picture clarity. Zbigniew Rybczyński’s 1990 hour-long art film, The Orchestra is not this. The very peak of technological editing prowess when it was released, its special effects have not aged well as we grow more accustomed to seeing the edges of the green screen, the lack of fidelity in the motion control as people’s feet move for no reason across a still background shot, and the original 4:3 presentation can’t upload neatly anywhere online. But to be clear, despite its age, The Orchestra is wonderful, more than thirty years since its release.

Polish immigrant Rybczyński had recently fled the State Socialism of the late eighties Eastern European block, and had established himself in New York, where in 1983 he had won the Academy Award for best Animated Short film. There’s an adorable clip of Matt Dillon and Kristy McNichol stumbling through trying to pronounce his name as they read the nominations and ultimate gave him his award. He’d gone on to direct a number of popular music videos for the likes of eighties giants such as Simple Minds, Yoko Ono, Lou

Reed, The Pet Shop Boys and even Mick Jagger, and his services were in high demand in an era where MTV could make or break careers. But in the late eighties he returned to more personal, experimental projects, which utilized state of the art motion control and blue screen technology to layer live action and pre-produced backgrounds together to stunning effect. The results of his innovations were combined into a series of six orchestral sequences, each one essentially its own music video, which told loose narratives around such events as the rise and fall of the Soviet Empire, love, loss and death, and the fusion of military and classical dance. The actors swirl and dance as much as they grieve and strive, and the overall experience of disorientation and seeing something truly unique is mesmerizing.

The opening sequence is a gentle journey around an imaginary garden, a garden of dreams, set to Mozart’s Piano Concerto 21. The camera glides and weaves through the greenery as elderly couples awake and reacquainted themselves with each other. The effect is hypnotic, and the perfect complement to Mozart’s concerto. But it’s all only prelude to the more sombre Sonata 2 from Chopin, more commonly known as the Funeral March, which sees hundreds of actors play individual notes on an infinite piano as they put their fingers on the keys, and then swiftly disappear. The sequence is sombre, melancholy, but completely captivating as the characters play their notes and then fade away into the digital ether. There’s a brief interlude where we follow a butler walking along an infinite series of walkways and platforms set to Albinoni’s Adagio in C Major, which begins to showcase Rybczyński’s motion control prowess to greater effect, but ultimately the sequence is fairly pedestrian in comparison to the tragedy of the previous funereal proceedings.

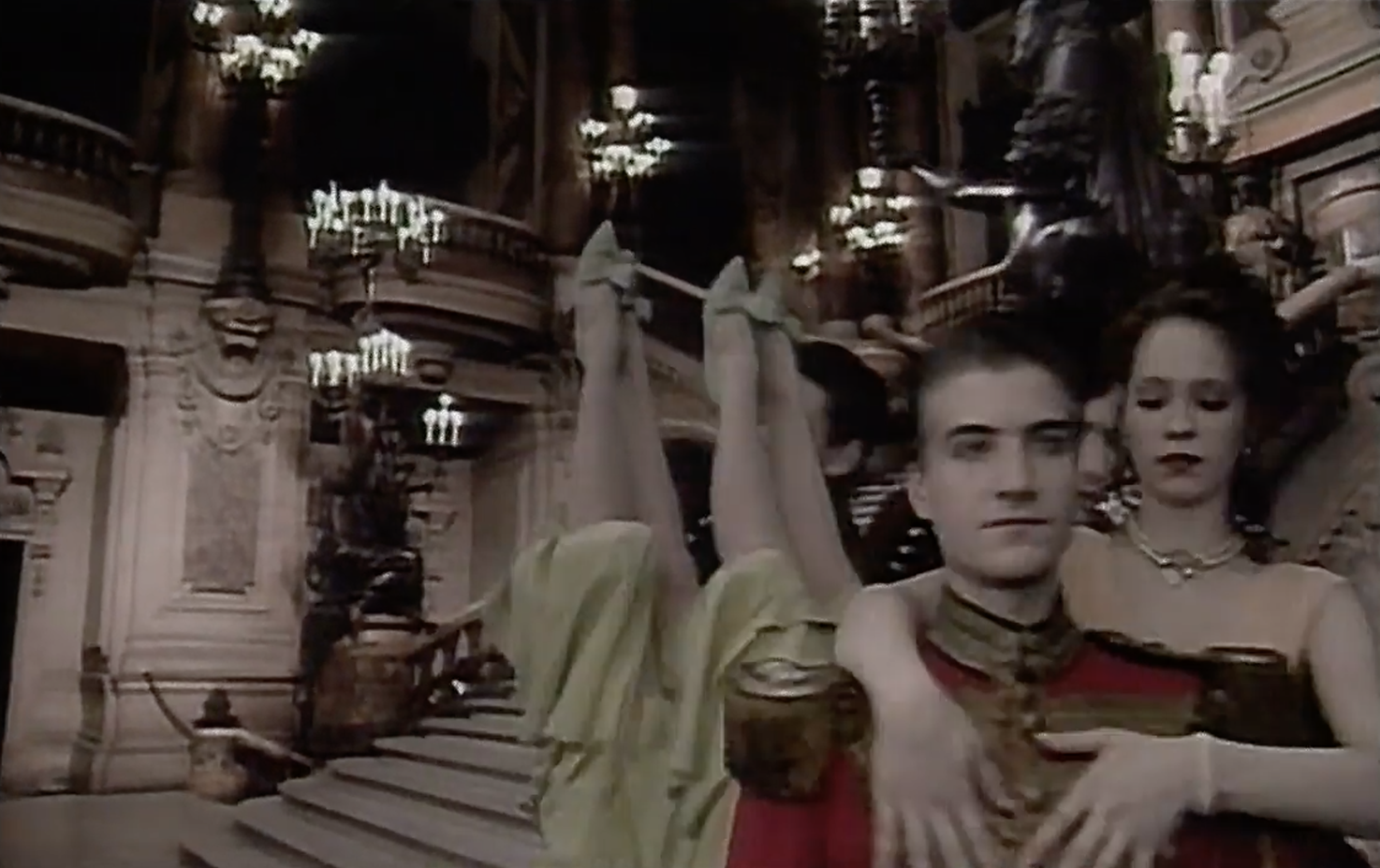

In one of the most glorious set pieces in the entire movie, the next sequence opens in one of the grand galleries in The Louvre, where Rybczyński had been granted exceptional access to film a series of backgrounds with his motion control rig. The rooms were filmed, and then the precise camera movements transcribed back into his studio in New York where they were digitally matched to live action he filmed and composited on top. Here the action ramps up and uses Rossini’s Thieving Magpie Overture as hussars, ballerinas and orchestral musicians dance their way past the enormous masterworks of Gericault, David and other giants of nineteenth century French Romanticism. In particular there’s some incredible shots of the ballerinas spinning in multiple takes that are so expertly timed with the swelling of Rossini’s score as to be truly magical. It’s in these moments where the more than thirty years of technological progress just melt away, and we enjoy it purely for what it is, a beautiful, innovative spectacle.

Parallel to the release of The Orchestra, Rybczyński released a short behind-the-scenes documentary about his specific process, where there’s a lot of focus on these sequences from The Louvre. Rybczyński goes into great detail about the often manual process of transcribing the score into beats he can use to trigger motion controlled shots, and we get to see just how painstaking the creation of it really is. A two second shot is filmed on the motion control rig in front of the blue screen matte, then played back in composited form as Rybczyński evaluates what to do and where to go next. There’s intense precision, but also intense labor, and insight into a craft which has long disappeared into the disintermediation of the digital editing suite.

Following the wonderful, energetic spectacle in The Louvre, next up is a trip to Chartres Cathedral where two naked figures soar effortlessly around the enormous interiors to Schubert’s Ave Maria before the grand finale takes place. Easily the most memorable of all six sequences, the final installment is set to the hypnotic Bolero by Ravel, and is the most narrative-driven of all the movements so far, telling the story of the rise and fall of state socialism and taking in about two hundred years of Russian history. The backdrop is an infinite, non-descript horizon, onto which hundreds of actors ascend an infinite staircase, passing items to each other as the elements of history unwind. We see familiar faces such as Stalin, Lenin, Trotsky and Fidel Castro, as well as generic-but-familiar soviet workers, KGB officers and Olympic champions. Ravel’s score swells in time with its relentless drum loop, and crescendos with the collapse of Communism, which at the time was happening in the real world just as much as it was in Rybczyński’s fabricated one.

Overall, despite its age, The Orchestra is still a wonderful artifact of the early days of digital video editing, and the sheer innovation and creativity inherent in this emerging technology. Rybczyński is an absolute master of the craft, and would go on to make a small number of other equally innovative short films of a similar nature, none of which really capture the breadth and depth of The Orchestra, and kept his hand in financially but continuing to make music videos, again another art form which lost its power in the age of streaming and downloads. But this isn’t a nostalgic lament for the analogue craft of the early days of technology. It’s a celebration of a genuinely masterful talent, and a shining of the spotlight onto an art film that truly captures what editing tools are all about, having as much fun as possible and creating some stunningly beautiful results.