It Was Easier When I Just Imagined You

Postcards from Paris, Texas (1984)

Wim Wenders’ 1984 movie Paris, Texas is one of those experiences that stays with you long after the credits have rolled. It certainly has for me, and even though I came late to Wenders’ films, his immigrant’s sense of wonder and amazement at the wide open spaces of the southern American landscape, and the personal stories of those who travel through them are something that, as an immigrant myself, have a deeply empathetic resonance and connection for me. To paraphrase what Alan Bates expressed in The History Boys, the best moments in watching movies are when you come across something – a thought, a feeling, a way of looking at things – that you'd thought special, particular to you. And here it is, set down by someone else, a person you've never met, maybe even someone long dead. And it's as if a hand has come out, and taken yours.

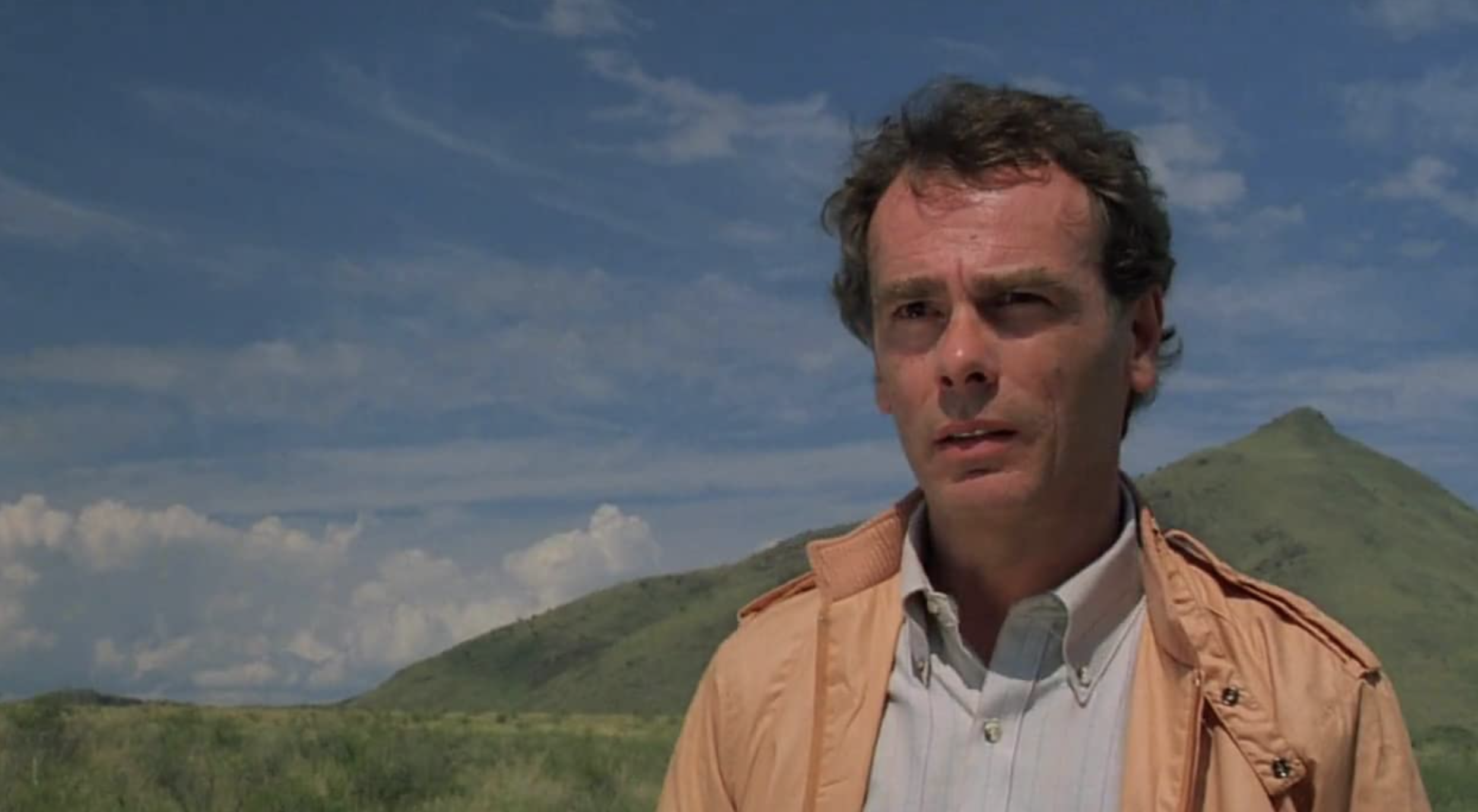

The movie opens with fatigue and desperation. Travis Henderson, clinically portrayed by the always excellent Harry Dean Stanton, is walking through the desert somewhere deep in the heart of Texas. He strides with conviction, but he’s at the end of his water, and the birds are starting to circle. Ry Cooder’s atmospheric score augments the contradiction of Travis’ extreme loneliness as he makes his way through the stunning landscape. It’s beautiful, but something’s wrong. We know nothing of Travis except he’s a man headed somewhere with purpose. But where, and why, not even Travis knows. This sets the tone for the rest of the movie, with unknown routes and destinations a recurring theme throughout. But ultimately it’s Wenders’ love affair with the road that connects the different narrative pieces of the story, and takes us as the audience along for the ride from A to B.

Travis stumbles across a small outpost literally in the middle of nowhere. Exhausted and dying from thirst, he attempts to drink from a long dead faucet. He eventually gets rescued by a kind local soul who takes pity upon him, and calls the number on his brother Walt’s business card, the only semi-recognizable piece of identification Travis still has with him. His brother, played with humility and grace by Dean Stockwell (who was later that year to star in David Lynch’s Dune), drives across country from his home in Los Angeles, and on the journey we get to indulge in some of Wenders’ most memorable visual love letters to the open road, something that will continue throughout the movie.

It’s not clear what’s happened to Travis, but we discover that he’s been missing for over four years in Mexico, and in that time, Walt and his wife have taken in Hunter, Travis’ young son. Suffering from acute mental trauma, Travis is unable to speak, won’t eat, and repeatedly attempts to resume his journey alone. Finally able to convince him to come back to Los Angeles together, Walt and Travis make the journey back to Walt’s home, and again we’re treated to the visual feast of traveling across the south western landscape, mainly at night, through the fluorescent, nicotine lens of truck stops, convenience stores and gas stations. You can smell the diesel-laced melancholy in every shot. Travis remains mute for much of the journey, sometimes to Walt’s frustration, but the familiar cinematic framework of our two main characters confined to the inside of the car with very little in the way of distraction on the highway leads to some wonderful, if mostly one-way exchanges. It’s clear that something awful has happened to Travis, and we spend most of the movie unraveling his story.

Reunited with Hunter, who’s understandably confused about who his real dad is, Travis begins to slowly reconnect with his son, and in one of the film’s most memorable scenes, walks him home from school in a truly tender display of father and son bonding through play. Travis is learning to be a dad again, but Hunter’s also learning to trust someone he’s only known in bedtime stories. But through it all, and conspicuous in her absence, is the specter of Travis’ estranged wife, Jane, who we learn is now living in Houston. Embarking on another long road trip, Travis and Hunter decide to try and find her, based on a scant number of clues to her whereabouts, and again Wenders indulges us in some truly breathtaking scenes of the American highway, punctuated by rest stops under overpasses, and some wonderful conversations between father and son that closely foreshadow events to come. Throughout it all, we still don’t know what happened between Jane and Travis, and he refuses to speak about it. But we do know that he needs to bring closure to the story between the three of them, and finally reunite his son with his mother.

Travis eventually finds Jane in Houston, working in a seedy part of town in an adult entertainment establishment that allows its customers to talk to women through a one-way mirror with the aid of a telephone. The women act out specific stereotypically submissive roles, and after a number of false starts, Travis finds Jane, portrayed with genuine sincerity and tenderness in her pink sweater by Nastassja Kinski. He asks her if she brings any of the customers home with her, and she tells him no. After a brief conversation, Travis leaves Jane without any resolution, but Jane recognizes his voice. Travis and Hunter spend the night in a nearby hotel while the downtown traffic of late-night Houston swirls below, and Travis resolves to go back the next day.

Upon returning, Travis and Jane find themselves in the booth again, and Travis tells Jane that he just wants her to listen to something he has to tell her. We then hear what happened between the two of them, and while I won’t give away the reveal here, as it genuinely is one of the most touching, heartbreaking and tender moments you’ll ever see between two estranged lovers, both Stanton and Kinski give outstanding performances of what went wrong between them, how Travis blames himself, and how he can never be with her again. Love will tear us apart, again.

The film ends with Travis successfully reuniting Hunter and Jane from a distance, but then Travis takes off into the night, destination unknown. Face illuminated by the dashboard and the passing billboards, our drifter casts himself out into the darkness, and just like Nick tells us at the end of The Great Gatsby, so we beat on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past.

Wim Wenders’ Paris, Texas takes us on a heartfelt and often painful odyssey of reunification through the romance of the American freeway. Those that find themselves on that journey are never sure of where they’re going or where they’ve been, but their love for each other is genuine, difficult, and long-lasting. It’s a film that will stay with you long after it ends, and repeated watching always turns up something new. In addition, Ry Cooder’s outstanding melancholic soundtrack is worth the admission alone, and transports us back to the contradictory nature of Wenders’ brilliant juxtaposition of the harshness of the landscape punctuated by the tenderness of those who find themselves passing through.

Latest Articles